Fifty years ago, when words like ‘bits’ and ‘bytes’ were gibberish to most people, a band of pioneers revolutionised the field of advanced control systems for cement applications. Using digitalization, these pioneers started to control the quality of cement, which has led to massive wins for reducing emissions and for improving the reliability of the end-product, concrete.

It was the year Apollo 11 landed on the moon. And while Neil Armstrong sat foot on the lunar surface and said, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” FLSmidth’s Henrik Bang-Pedersen and his colleagues in the electrical department took one small step in cement production that pointed the way to a giant leap for the entire cement industry. FLSmidth’s QCX® (Quality control by Computer and X-ray) system applied basic analyses to quality testing throughout the cement production process, which revolutionised how we produce cement and our ability to construct skyscrapers, bridges and dams.

How the QCX system changed the game

Today, the QCX/BlendExpert™, part of the QCX software suite, represents a paradigm shift in the industry – similar to what Hoover did to the vacuum cleaner market - it became a synonym for software that optimises cement quality. By scanning and analysing the raw mix and clinker, the QCX/BlendExpert™ ensures control of the cement’s chemical properties and, ultimately the quality of the concrete.

Even though the original QCX was not as intelligent as it is today, the technology and its ability to optimise the quality of cement had a major impact on cement production, including our ability to build larger concrete structures. Most importantly, the QCX technology has played a major role in reducing CO2 emissions from the cement production process.

Fifty years ago, one kilogram of cement generated more than 900 grams of CO2. Today, that amount is down to 570 grams. At least one third of that reduction is attributed our ability to better control the production process and optimise its quality. Most recently, with the latest version of the QCX/BlendExpert™, the improved process modelling and optimisation has led to a 2% reduction in energy consumption.

The people behind the patent

One of the key drivers behind the ground-breaking innovation was Henrik Bang-Pedersen, who joined FLSmidth after graduating Technical University of Denmark (DTU) with his engineering degree in 1967.

Bang-Pedersen was charged with introducing computer controls in the cement industry. The combination of a Masters in Chemical Engineering and a specialisation in automation and the application of software, Bang-Pedersen had the unique perspective to integrate these capabilities into a combined solution.

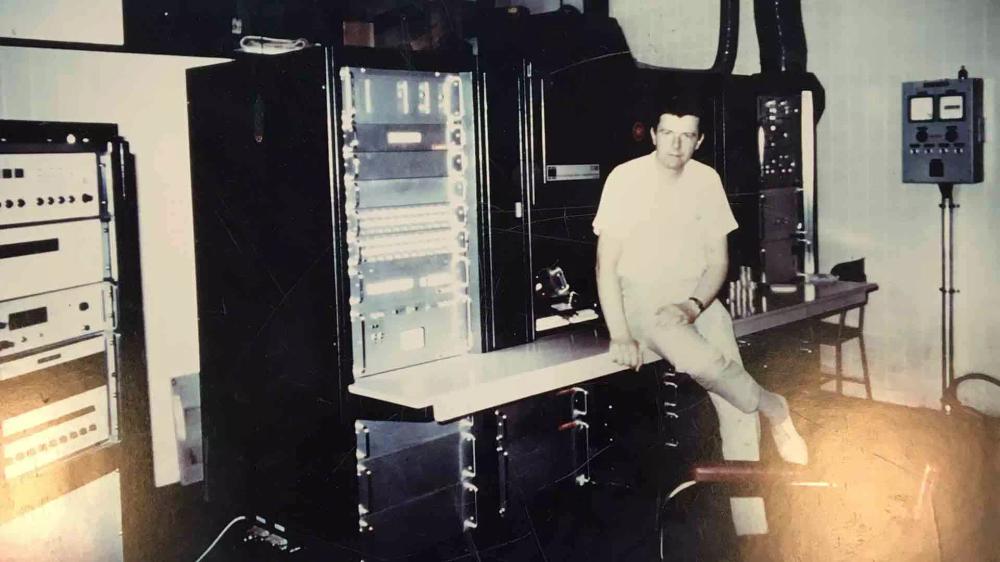

HENRIK BANG-PEDERSEN

He was convinced there was a way to use computer processing power to improve the management of the raw meal quality and give operators better control. At the same time, Bang-Pedersen and his team were closely following developments in computing technology. Although processing power was still rather limited, it was beginning its early rise to fame.

Bang-Pedersen admits it is satisfying to see how far the system has come along in last 50 years and has fond memories of his pioneering team and their peculiar way of working.

For Bang-Pedersen, the progress of QCX was the launchpad for the remainder of his career. He later held senior management roles at FLSmidth, was the CEO of an electrical engineering company, and Chairman of the Danish Automation Federation.

Development of the QCX began in 1969, with its first customer implementation in 1970. To date, there have been more than 800 installations. The first system was commissioned by Peter Krüger (picture).

Worth the risk

After its early successes, it became apparent that the QCX/BlendExpert™ had great potential. To keep the progress moving forward rapidly, Bang-Pedersen was allocated more resources and began to grow the department; “We had to take risks, perhaps in a way that hadn’t been possible before,” he says. “We were probably the odd ones out, as we didn’t work according to the same processes as most of our colleagues at the time. But we needed to work fast, and we couldn’t always wait for formal approvals.”

At the same time, effort had to be put into sales. As with any new system, customers had to be made aware of its benefits and how to apply this new technology to add value for their operations.

While there were learnings required internally at FLSmidth and for customers, one of the fundamental design principles was ease of maintenance. Ease of maintenance still remains a key feature, but it was more critical at the time as speed of communication and the ability to provide fast assistance was nothing like it is today. “Remember, there was no mobile phones, no internet or email in those days. It took longer to help customers solve problems. Commercial success demanded that we make it simple. In contrast to the much larger computers of the day, the required maintenance of the QCX/BlendExpert™ had to be extremely low."

The small step

Ambition increased when Bang-Pedersen and his colleagues realised there was a clear opportunity to achieve an industry first. But behind the technological ambition was a clear commercial objective.

HENRIK BANG-PEDERSEN

Within a few months, the product had its first customer in Thailand, where the system was implemented in 1970. It saw steady growth over the next few years, quickly spreading throughout the international world of cement production. Within a decade, QCX/BlendExpert was established in plants in Europe, South Africa, Poland, DPR Korea, Romania, Portugal, Greece and several other countries. To date, there have been more than 800 installations of the system and its subsequent versions.

A compact solution

What made this innovation so special as to spark a cement industry phenomenon across multiple countries and versions? That’s an easy question for Bang-Pedersen to answer: “It was the first very compact system that enabled operators to get computer control based on analysing the raw mix blend with x-ray technology. We created something so much smaller than the rather few, large computing systems available at the time.”

This was merely a sign of things to come. The QCX/BlendExpert™ was initially designed as a system for automatic control, whereas the monitoring and reporting was later expanded to cover the entire plant processes.

In today’s world, the first version’s eight KB (kilobyte size) was incredibly small compared to today’s gigabytes. However, in those initial days, those few bytes were monumental. “It’s funny to think that we were impressed by eight KB, but even then, it made a difference to the way we could analyse raw meal. We could by computer communicate with the x-ray equipment and the raw mill’s control system to control the raw mix. It meant we achieved a faster, better control of the raw mix”.

Making a mark on the modern world

If the original version was like landing on the moon, today’s latest version, is like stepping onto Mars. Today's QCX/BlendExpert™ has processing power of many GB’s (gigabyte) and the capacity to operate an unlimited number of feeders. Back in 1969, the system was limited to only three.

“Once this was seen in action, we began to believe even more in the potential and where it could lead,” says Bang-Pedersen.

It was the first step to replacing repetitive, laborious manual tasks that relied upon an operator's skill and judgement. Previously, an operator would adjust the raw mix by turning knobs on a manual control panel according to his or her interpretation of wet-chemical laboratory analyses and manual raw mix calculations. The QCX/BlendExpert™ would now do this automatically, allowing more consistent quality control.

Leading the way in innovation and commercial viability, there’s no doubt Bang-Pedersen and his team have left their mark on the cement world.

One small step for man...

In 1969, the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) was used to launch and guide the Apollo 11 space shuttle to the Moon and back. This rope memory for the (AGC) was made by hand, and was equivalent to 72 KB of storage. In comparison the QCX from FLSmidth operated with a 16 KB core memory.

Hewlett Packard, which the year before had launched the world's first personal computer, was the main supplier of hardware for the QCX.